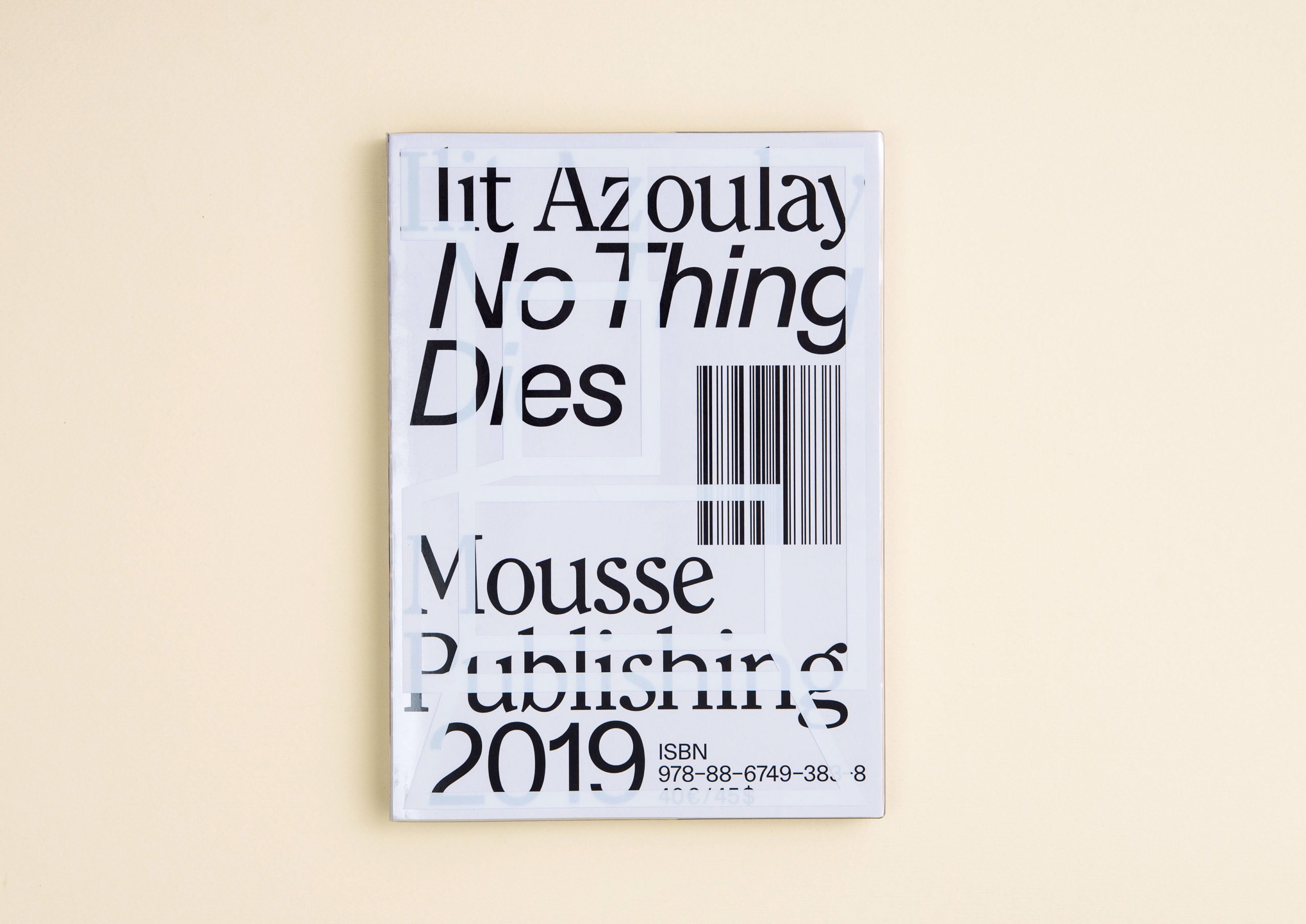

Publications

No Thing Dies

Mousse Publishing, 2019

ISBN 978–88–6749–383–8

40 € / 45 $

Edited by Maurin Dietrich

Introduction

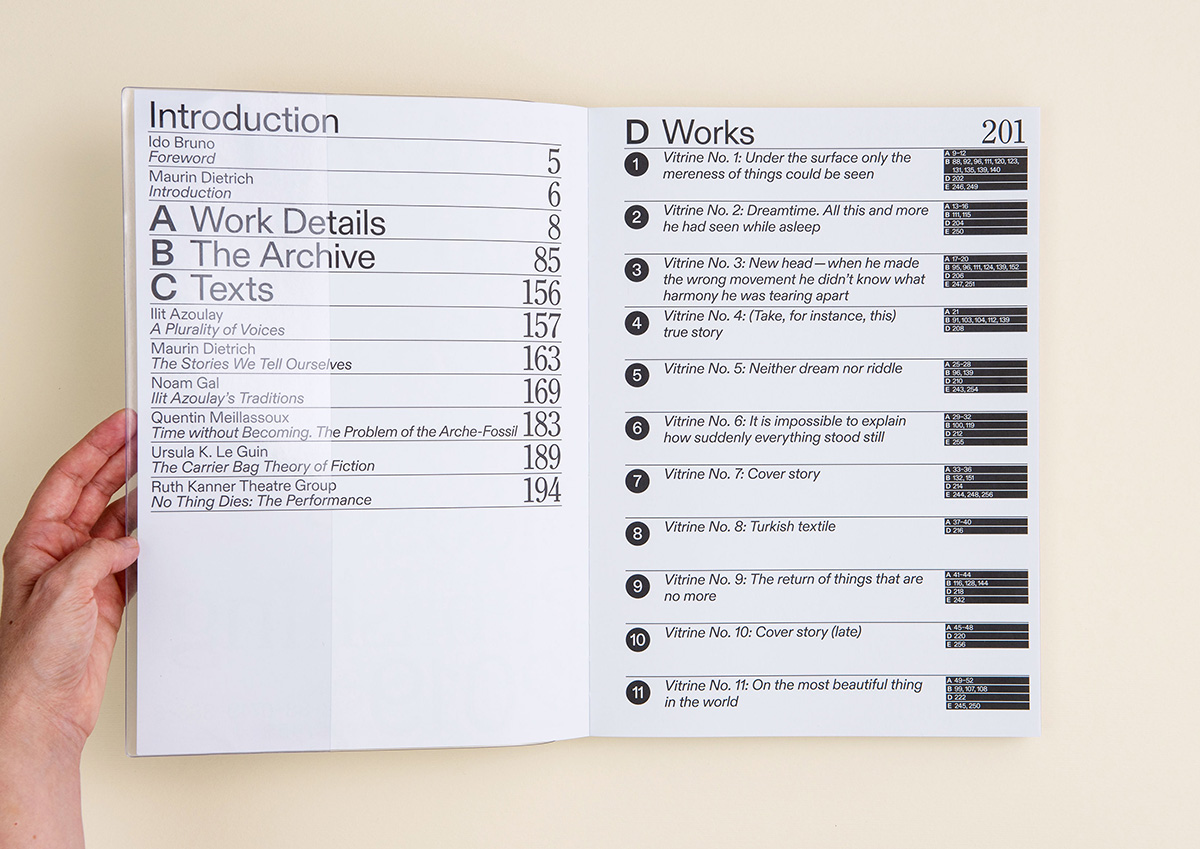

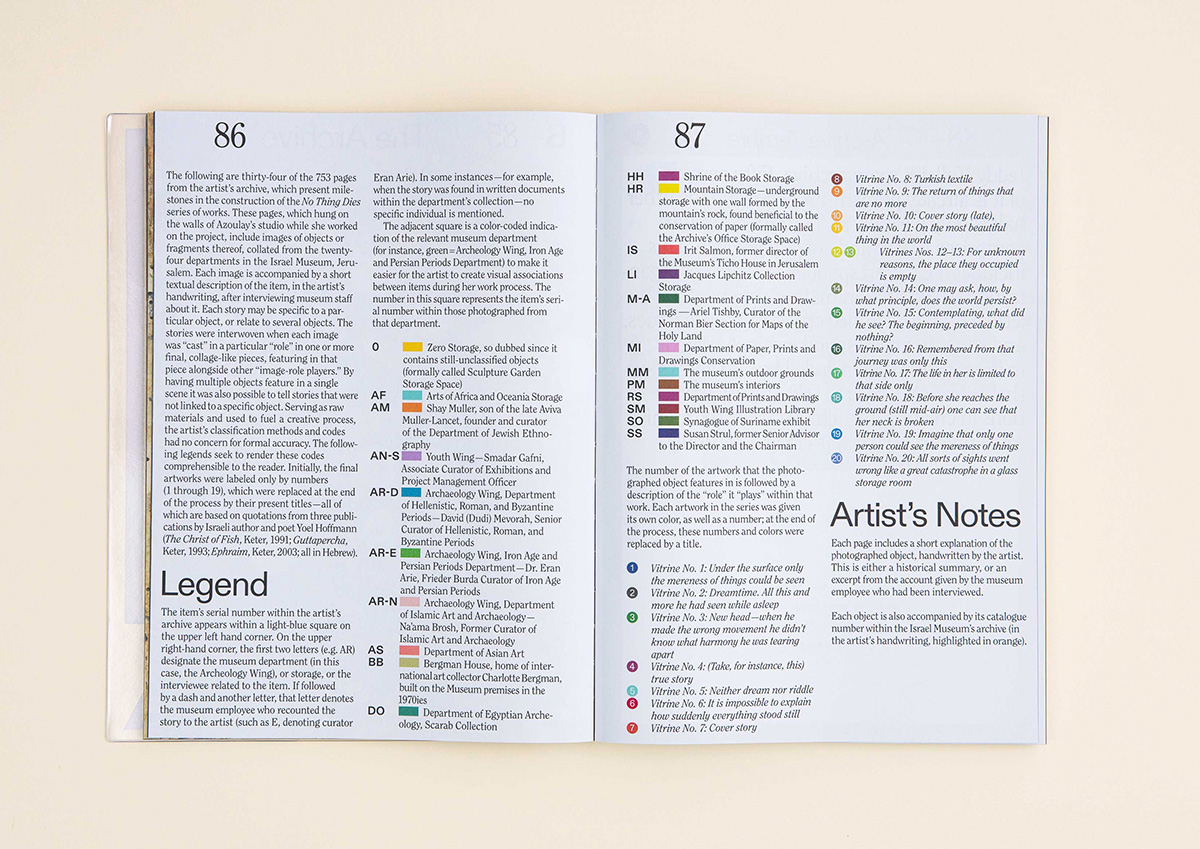

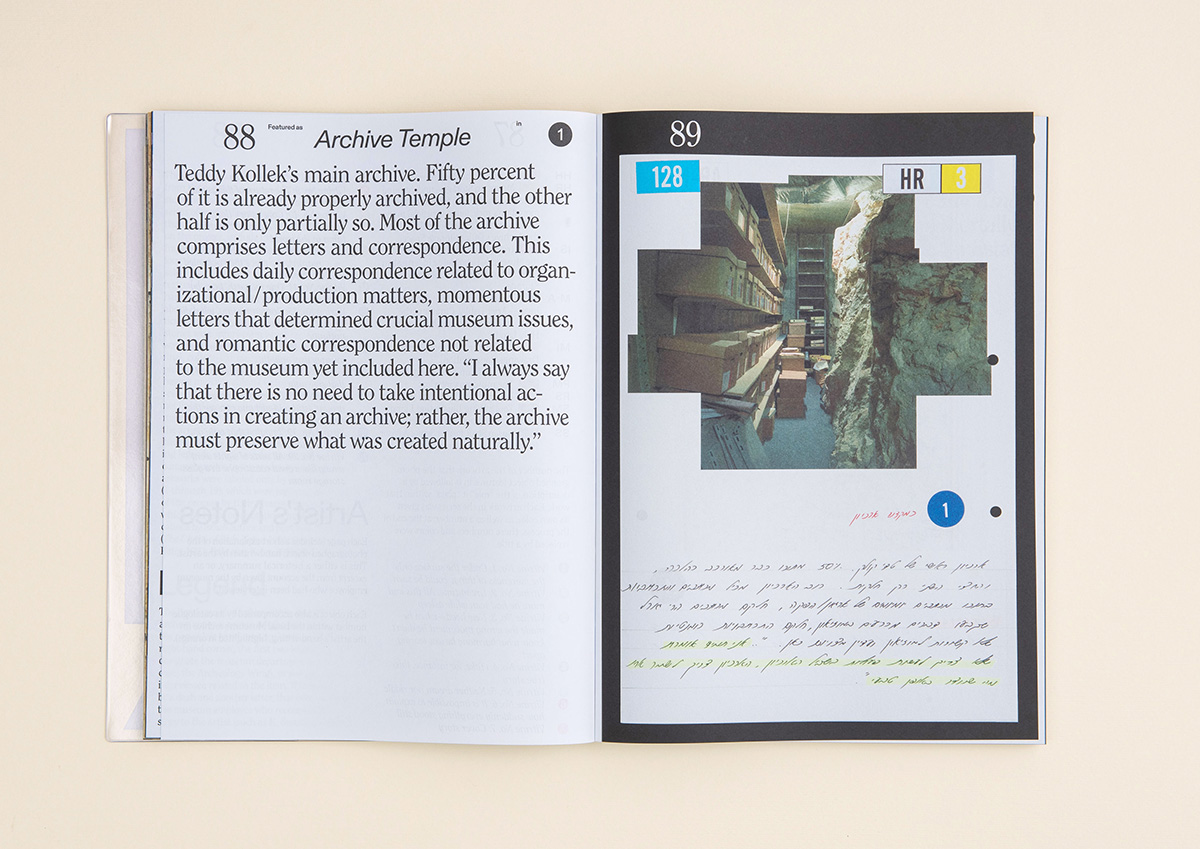

This publication brings together images and archival materials related to Ilit Azoulay’s No Thing Dies project, as well as illuminating texts by authors from different fields. One of the starting points in putting it together was the extended research conducted by the artist into the collections of The Israel Museum, Jerusalem, in preparation for her exhibition there (June to December 2017). The project raised the question of how such an institution gives shape to a collection of objects and, consequently, gives voice to certain histories while silencing others.

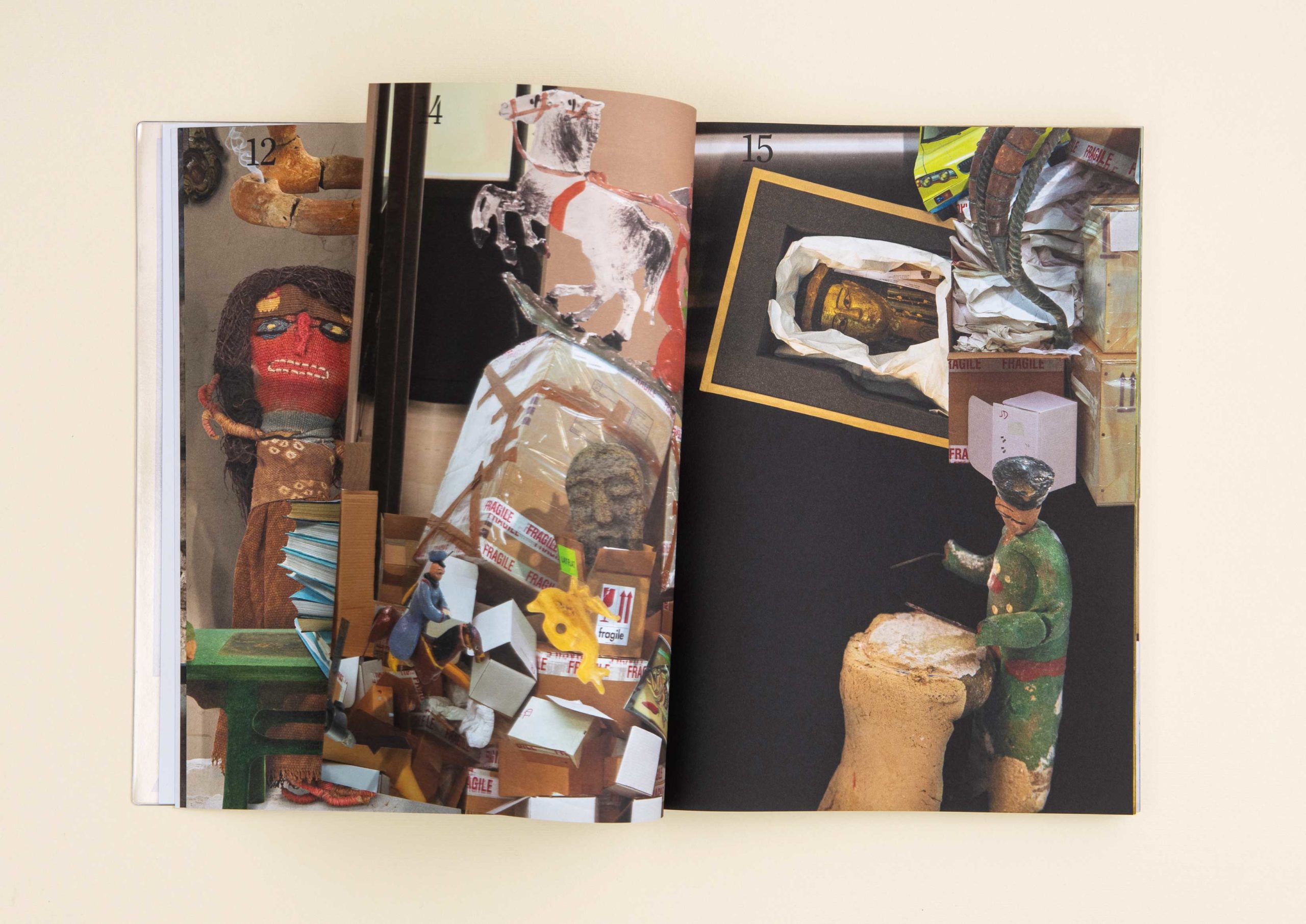

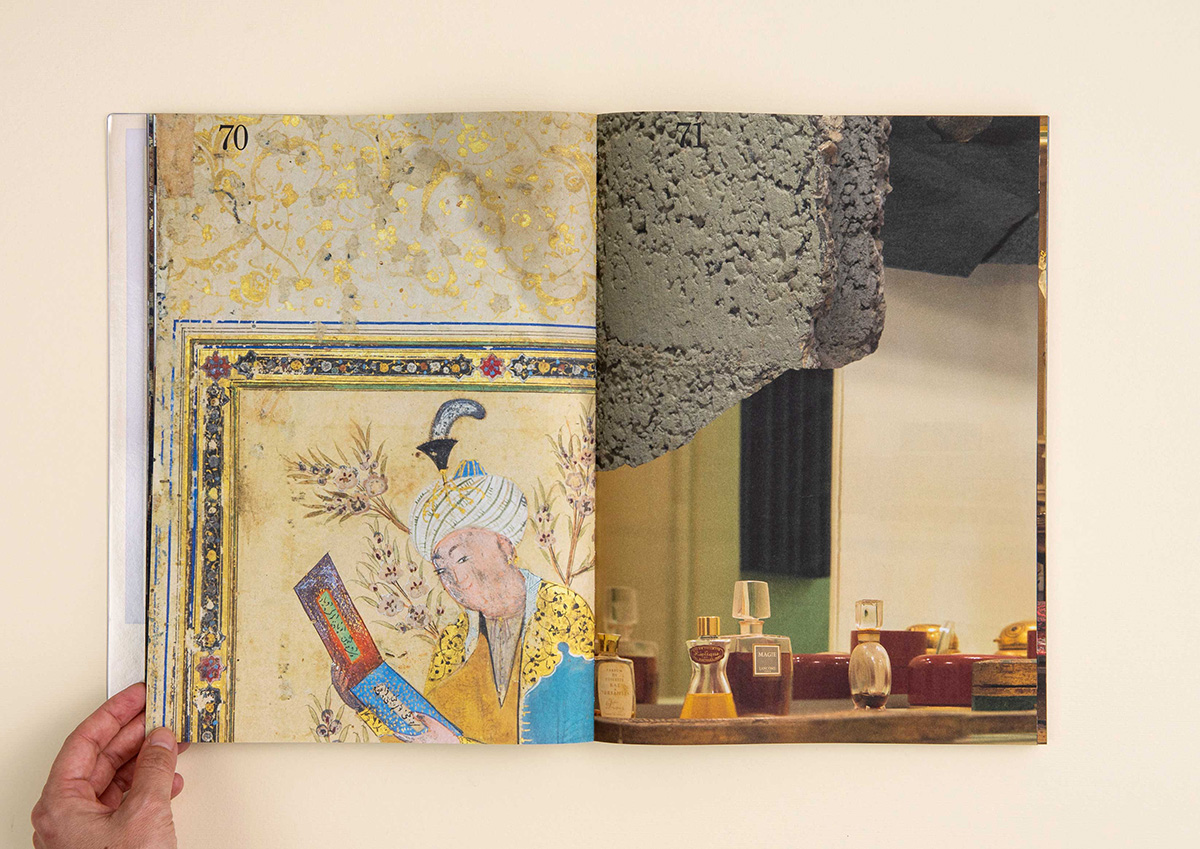

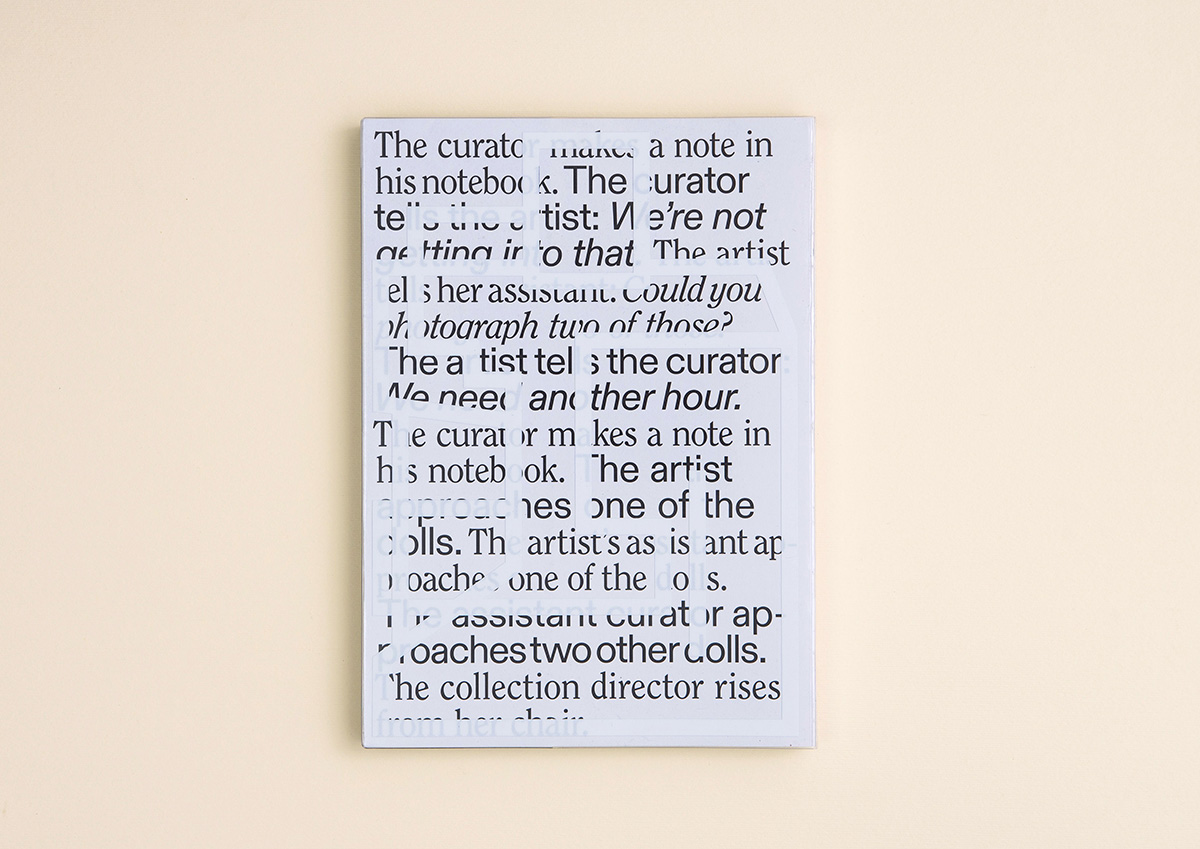

The project started with the artist listening to the stories of the people in charge of the museum collections and the items within them. For her, storytelling is a way of passing on history and its complexity in a manner unequaled by any other form of transmission of accumulated knowledge and culture. Eventually, this contributed to her articulating a critique of this encyclopedic museum, which is not habitually presented in its exhibitions or catalogs. With her team, she recorded many such stories. She then revisited all the departments and photographed every single object that was mentioned.

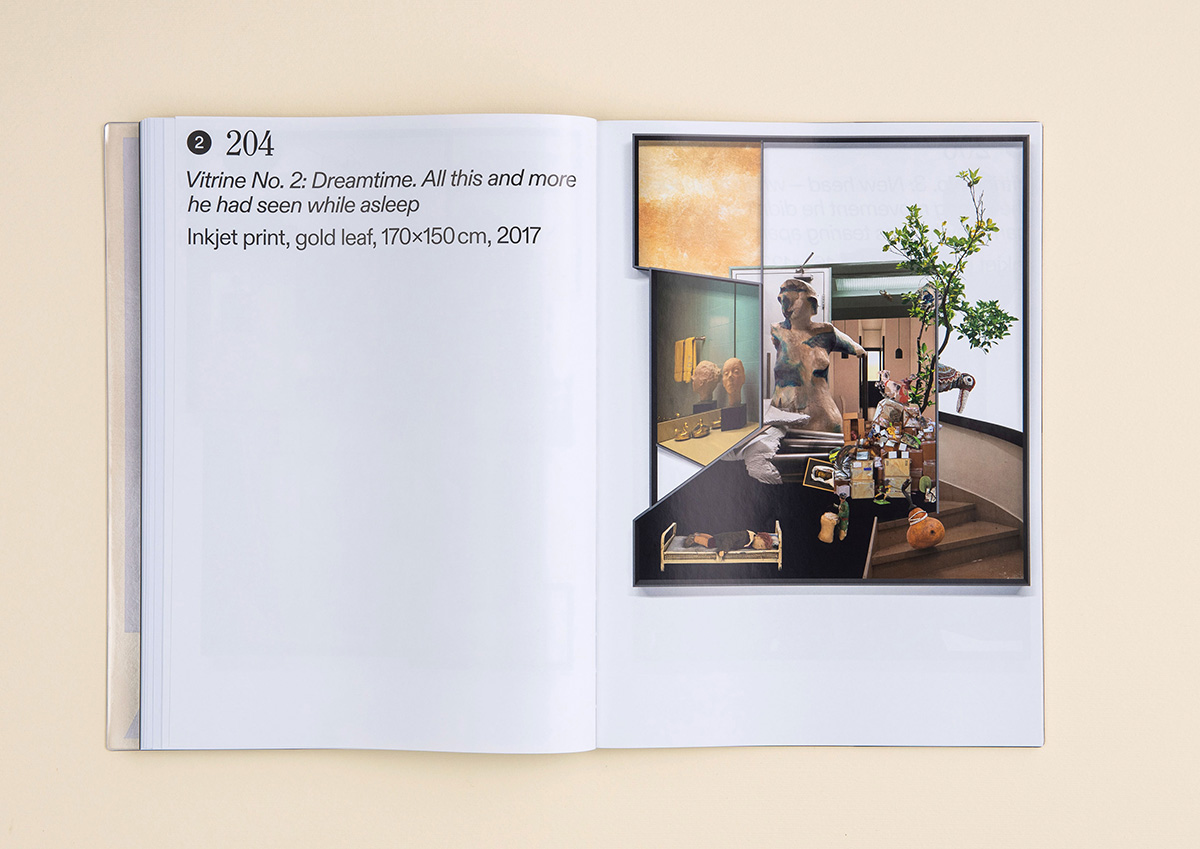

The photographic method Azoulay used in this, as in most of her other projects, is unique. To capture the image of each object, she uses a digital camera with a macro lens and takes several shots of it, moving upward along the surface of the standing object as though scanning it. She then stitches these images digitally, in Photoshop, into a single image. The result is a very high-definition image of the object, often exceeding the resolution our eyes are capable of.

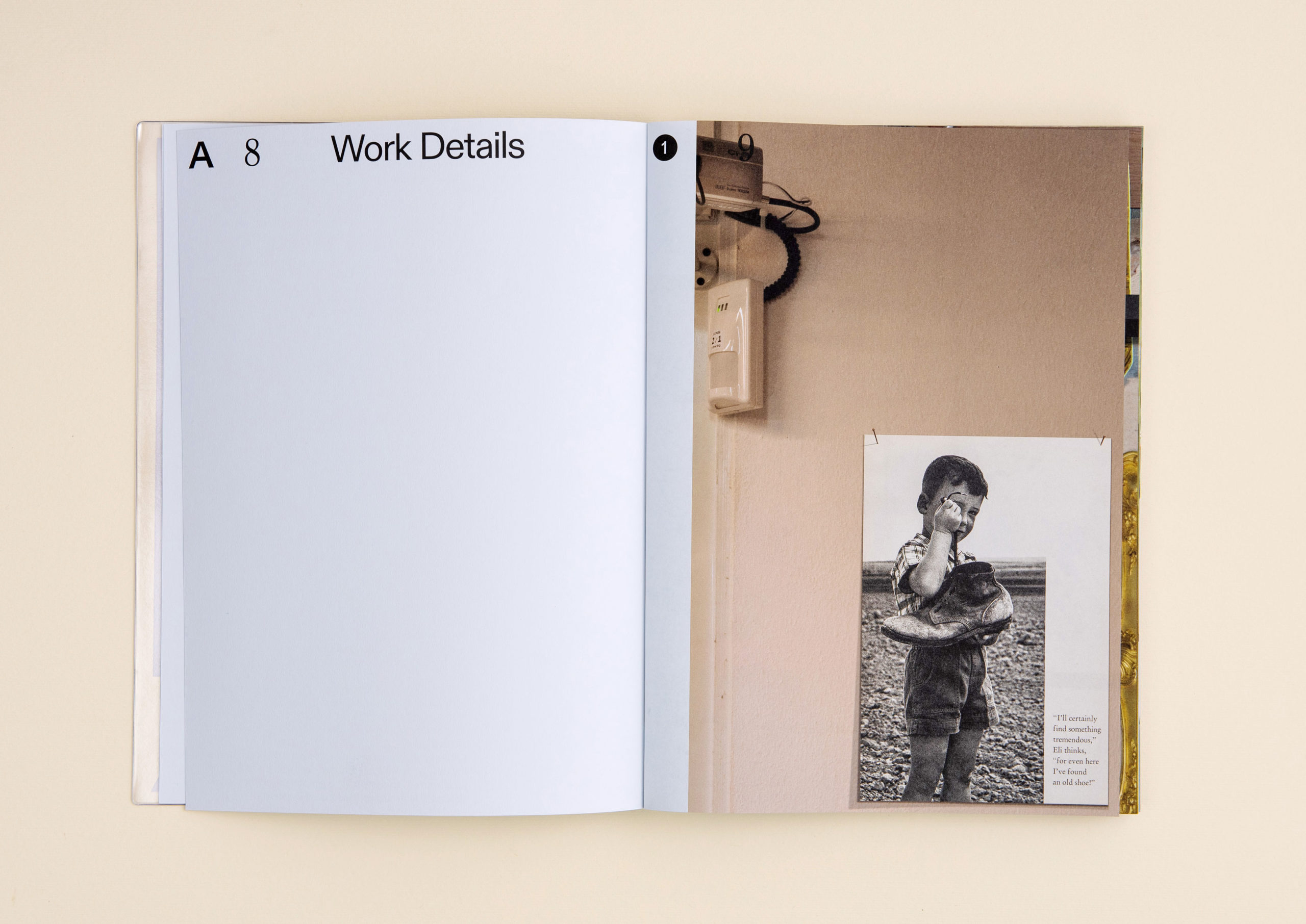

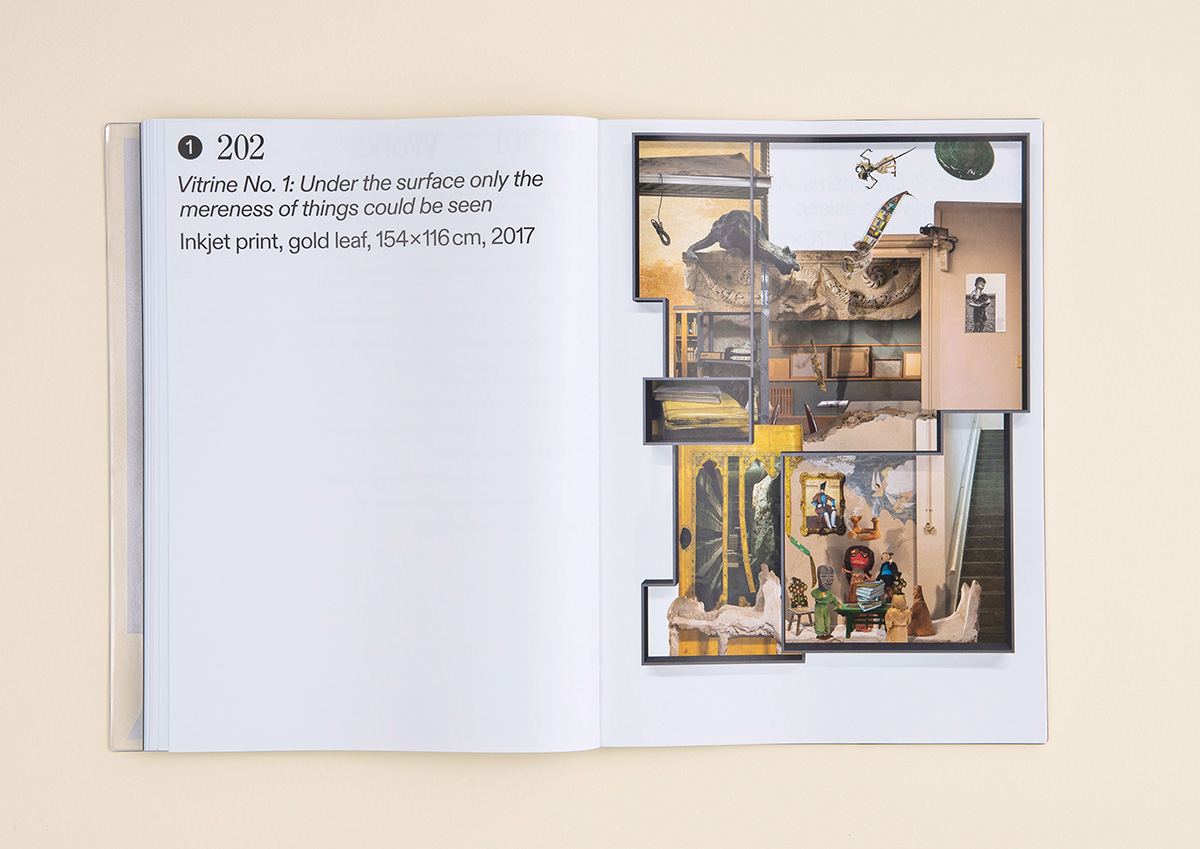

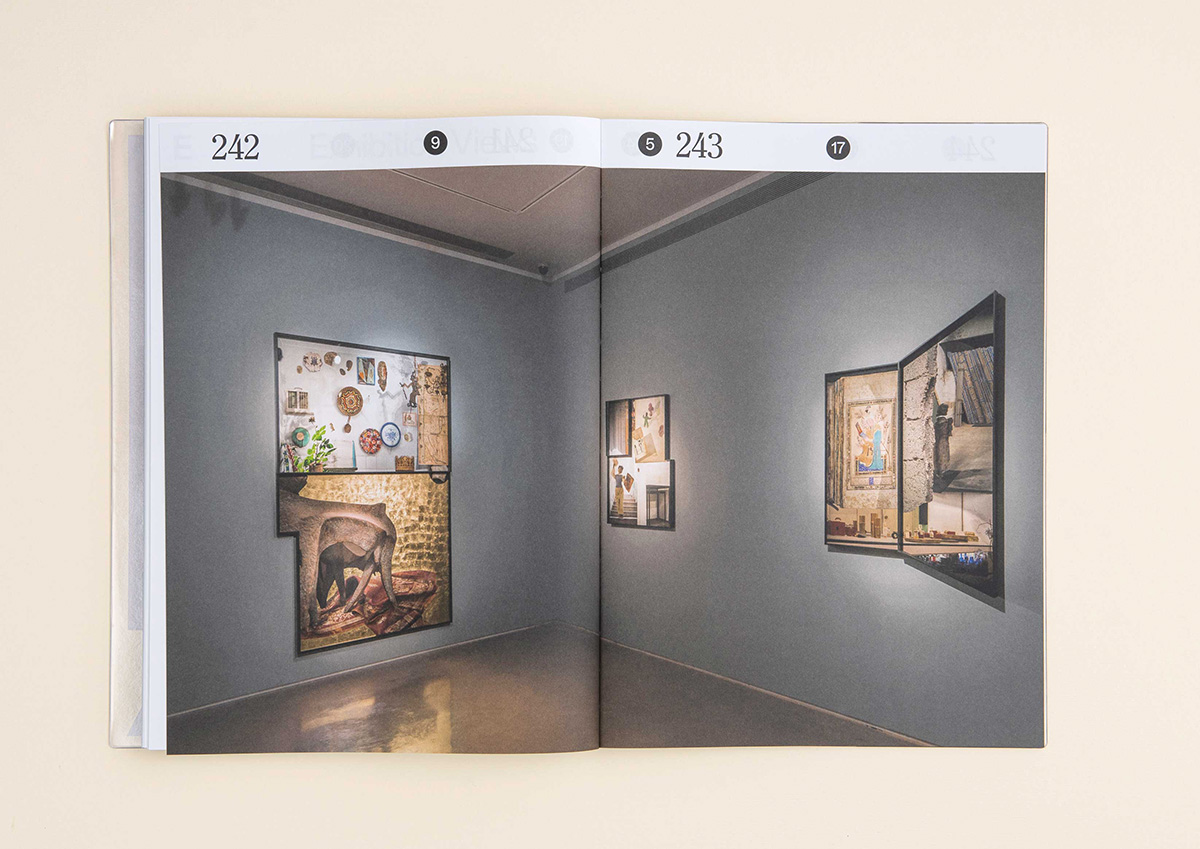

By this method, Azoulay acquired the images of 753 objects (or fragments) from 24 different departments, which she came to view as raw data or “archive pages,” a selection of which is included in the book. Then, she composed scenes to conjure up the histories evoked by the interviews, constructing novel interactions between objects (cast as characters) and creating “stages” for them. Hierarchies were shuffled, inter-department boundaries were removed, all elements became contingent upon the stories told by the complex images Azoulay assembled. Every one of the final works consists of numerous sections, each comprised of multiple details, spaces, and perspectives, merging time periods, spheres, perceptions, and modes of representation.

The photographic images, thus stitched together, were then placed in three-dimensional display-like casings – vitrines (as the artist dubbed them) – each comprising several sections enclosed within frames of varying depth. In this way, each work is presented as a photographic diorama that, much like a Persian miniature, offers multiple windows onto a possible page in local history.

In the book devoted to this project, the reader is invited to wander among the images composed by Azoulay from the museum’s many stories and artifacts in an effort to give expression to their fascinating, polyphonic, and multifaceted viewpoints.