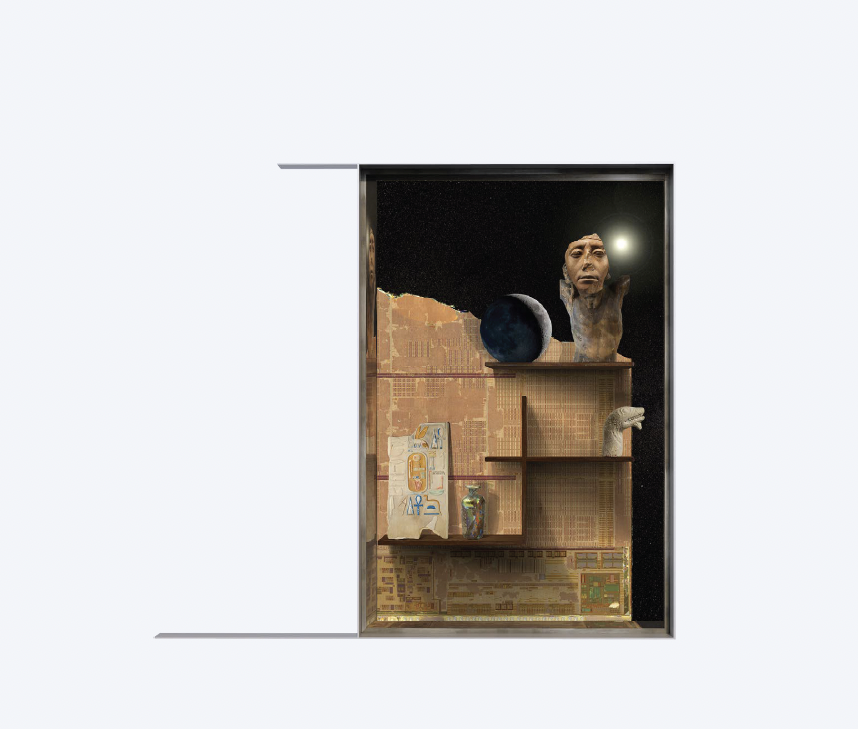

Ilit Azoulay lives and works in Berlin. Her photographic background emerges from research-based scrutiny, engages with archiving and history, and creates alternative perspectives. Her works break down hierarchies of time and space by overlaying multiple realities and explore alternatives to male-dominated or Eurocentric forms of storytelling and knowledge transfer. In doing so, she deconstructs the notion that photography is meant to capture a decisive moment. Incorporating photomontage, sound, and architectural elements, Azoulay examines how visual information travels and is processed culturally, economically, and politically.

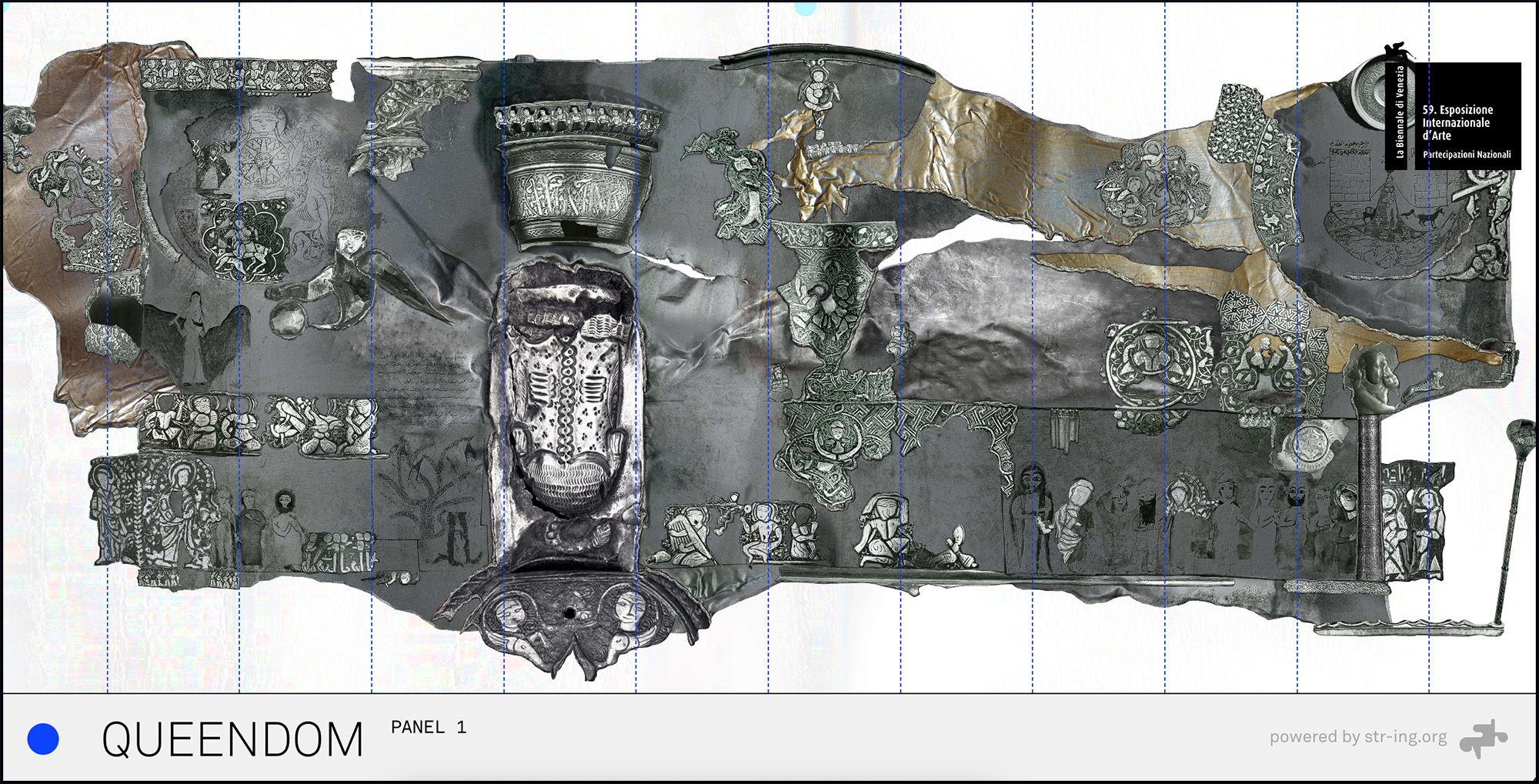

Ilit Azoulay’s work has been exhibited extensively and internationally in galleries and museums. In 2022, the artist represented the Israeli Pavilion at the 59th Venice Art Biennale with her project Queendom.

Ilit Azoulay

2024 Mere Things, Jewish Museum New York

2024

Mere Things, Jewish Museum New York

QUEENDOM. Navigating Future Codes, Museum der Moderne, Salzburg

Common Ground, The Israel Museum, Jerusalem

2023

Queendom, Lohaus Sominsky Gallery, Munich

Gedanken Spielen Verstecken, Haus Kunst Mitte, Berlin

European Month of Photography, Berlin

2022

Expanded Visions. Photography and Experimentation, CaixaForum Madrid, Madrid, Spain

Queendom, Israeli Pavilion, 59th Venice Biennale, Venice, Italy

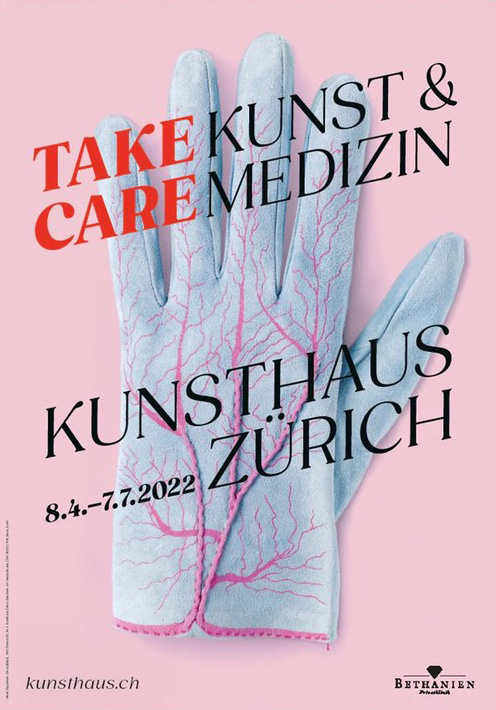

Take Care: Art and Medicine, Kunsthaus Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland

2021

Mousework, Braverman Gallery, Tel Aviv, Israel

Hope – Prix Pictet, Eretz Israel Museum, Tel Aviv, Israel

2020

Skɪz(ə)m, Plato Ostrava, Czech Republic

31: Women, Daimler Art Collection, Berlin, Germany

La Colère de Ludd, New Acquisitions, 40 BPS22 – The Art Museum of Province de Hainaut, Charleroi, France

2019

Regarding Silences, CCA, The Center for Contemporary Art, Tel Aviv, Israel

Transferumbau: Liebling, White City Center, Tel-Aviv, Israel

Transferumbau: Dessau, Bauhaus Museum Dessau, Germany

2018

The Big Picture, Nelson – Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri, USA

Kedem-Kodem-Kadima, CCA – The Center for Contemporary Art, Tel Aviv, Israel

No Place Like home – Museu Coleção Berardo, Lisbon, Portugal

Daegu Photo Biennale 2018 – Daegu, South Korea

Excavation Mark! Reveal Preserve Glorify, Hansen House – Centre for Design, Media and Technology, Jerusalem, Israel

2017

No Thing Dies, The Israel Museum, Jerusalem, Israel

Nebraska: unknown aspects, Braverman Gallery, Tel Aviv

2016

Photography Today: Distant Realities, Pinakothek der Moderne, Munich, Germany

2015

Ocean of Images: New Photography 2015, MoMA, New York, USA

A Seventh Option, Andrea Meislin Gallery, New York, USA

The Biography of Things, The Australian Center for Contemporary Art, Melbourne, Australia

Les Rencontres d’Arles Discovery Award, nominated by Quentin Bajac (MOMA), France

Disorder: Prix Pictet Finalists, Musee d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, France

[7] Places [7] Precarious Fields, Fotofestival Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany

Affinity Atlas, The Frances Young Tang Teaching Museum and Art Gallery at Skidmore College, Saratoga Springs, NY, USA

Re:Start, Braverman Gallery, Tel Aviv, Israel

2014

Implicit Manifestation, Herzliya Museum of Contemporary Art Shifting Degrees of Certainty, KW, Berlin, Germany

Altarations: Built, Blended, Processed, Schmidt Centre Gallery, Florida Atlantic University, Florida, USA

The Double Exposure Project, Shpilman Institute For Photography, Tel Aviv, Israel

2013

Linguistic Turn, Braverman Gallery, Tel Aviv, Israel Room#8, Andrea Meilsin Gallery, New York, USA Collecting Dust in Contemporary Israeli Art, The Israeli Museum, Jerusalem, Israel

2012

Tree For Two One; Public Installtion, Contact Photography Festival, Museum of Canadian Contemporary Art, Toronto Misplaced, Displaced, Replaced, Rotwand Gallery, Zurich, Switzerland Eyes in the back of the head, The Israeli Center for Digital Art, Holon, Israel Private/Corporate VII, The Doron Sebbag Art Collection, Tel Aviv, in collaboration with the Daimler Art Collection, Stuttgart/Berlin

2011

The Keys, Andrea Meislin Gallery, New York, USA The Constantiner Photography Award for an Israeli Artist, Tel Aviv Museum of Art, Tel Aviv, Israel Magic Lantern: Recent Acquisitions in Contemporary Art, The Israel Museum of Art, Jerusalem, Israel The Fabulous Eight Or The Mysteries Of The Enchanted House, 27 Hissin st, Tel Aviv, Israel Numerator and Denominator, Herzliya Museum, Herzliya, Israel

2010

The Keys, Bezalel Academy of Art and Design Gallery, Tel Aviv, Israel New in Photography: Recent Acquisitions, The Israel Museum, Jerusalem, Israel

2008

Art Harvest, Art Farm Residency, Nebraska, USA Findings, Minshar for art Gallery, Tel Aviv; Israel

Awards

2017

Israeli Culture and Sports Ministry Prize Artis Project Grant Outset Project Support

2015

Artis Exhibition Grant

2013

Mifal HaPais Foundation Grant

2011

Israeli Culture and Sports Ministry prize The Constantiner Photography Award for an Israeli Artist, Tel Aviv Museum of Art

Collections

Art Institute Chicago, USA

Centre Pompidou, France

Daimler Art Collection, Germany

Doron Sabag Collection, Israel

Elstein Collection, Israel

Guggenheim Museum, New York, USA

Hainaut Province Collection, France

Hangar Photo Art Center, Belgium

Igal Ahouvi Collection, Israel

Julia Stoschek Collection, Germany

Knesset Israel (the Israeli Parliament) Collection

LACMA, USA

Rivka Saker Collection, USA/Israel

Mandel Collection

MoMA – The Museum of Modern Art, New York, USA

National Gallery of Australia

The Ekard Collection, Netherlands

The Herzliya Museum of Contemporary Art, Israel

The Israel Museum, Jerusalem

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, USA

The Tel Aviv Museum of Art, Israel

Tiroche de Leon, Israel

Tony Podesta Art Collection, USA

Yona Fischer Collection, Israel

Ashdod Art Museum – Monart Center, Israel

SIP – The Shpilman Institute for Photography, Israel